To the architects of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the sweeping reform was a quick cure-all for what was ailing Corporate America’s moral structure. But as public companies struggled to get their hands around compliance, and particularly onerous Section 404 requirements by the December deadline, they’ve shelled out millions of dollars to auditors, accountants and consultants. There seems little argument that the pendulum has swung too far.

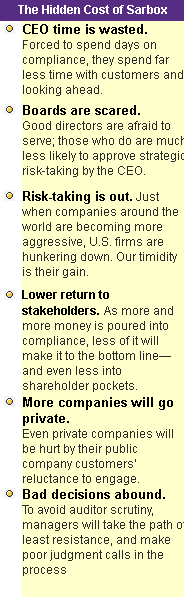

With chief executives now personally accountable for every uncrossed “t”, they’ve been challenged to design new ways of managing their companies’ information flows so that they have a private window into all that goes on. That might be a good thing—assuming it’s possible. But while legislation that forces companies to pay more attention to potential malfeasance is certainly positive, most CEOs view Sarbox as a hastily written, poorly conceived law that will have years, if not decades, of unintended consequences for U.S. companies

The overhaul has proved particularly painful for those CEOs who believe they already had sufficient checks and balances in place, and are now finding that the everyday added compliance demands are draining corporate coffers and CEOs’ time, causing U.S. companies to hunker down in defensive, risk-averse mode at the worst possible time. In other words, CEOs agreed at a roundtable, reform is good—but the very legislation that aimed to protect shareholders now stands to harm them. “We’re out of balance,” said Pat Russo, CEO of Lucent Technologies, “and there is an ultimate price we’ll pay for staying out of balance.”

Part of that will be the literal price tag—the enormous cost of compliance, which is taking a huge bite out of companies’ bottom lines. Eugene McGrath, CEO of New York utility Con Edison, said Sarbox cost $2 million to $3 million to the bottom line “just to pay the extra accountants and all the attorneys to watch over everything we did.” He added that, on a more positive note, the company’s stakeholders will have assurance that the company is run ethically.

But will that justify the 1 to 2 percent off the bottom line for the investor? Not necessarily. “The costs so far outweigh the benefits. It’s unreal,” said Robert Ashe, CEO of business intelligence solutions company Cognos, which sponsored the roundtable. “The things that the auditors are doing are just unbelievable.”

In the new world of hyper-regulation, it will be auditors, not shareholders, who profit most—and auditors are fully aware of their advantage. “They are gouging,” said Al Fasola, director at cable company RCN. “They’re getting higher returns from every individual in the firm at a time when they’re risk-managing their way out of the accounts that may cause them legal briefs in the future. They’re reaping a huge windfall.”

Meanwhile, as expenses mount, companies are losing productivity to the compliance grind. “There’s the lost opportunity of spending time on doing a deal with a customer so I can generate value versus spending time on internal, process-oriented issues,” said Russo, who calculates that she spends at least half a day at each quarter’s end with finance specialists, lawyers and binders full of certifications. And that’s not counting the unexpected time-draining events, such as one long, drawn out tug-of-war Russo recalled having with Lucent’s accounting firm about a matter that should never have been on her calendar. “It was a month’s worth of time,” she said.

For Con Edison, the focus on compliance is such a strain, it could put future growth at risk. “Prior to Sarbanes-Oxley, our people were working 80 or 100 hours a week,” said McGrath. “So Sarbanes-Oxley comes along and I think the big management issue for us is, How do we manage Sarbanes-Oxley and not take our eye off the ball and get into real trouble with the business?”

That is a challenge on multiple fronts. First, the new obsession with rules and regulations is creating a culture more of avoidance and fear than of entrepreneurial ingenuity. “The reason the United States industry has been successful is we’ve been aggressive,” said Donald Nigbor, chief executive of Benchmark Electronics, a service provider and electronics manufacturer. “We’ve taken risks; we’ve gone out and promoted new technologies; we’ve done all these things over the years, and now we’re pulling back.” That hunker-down mentality, he added, is taking root at the board level, filtering down through the organization, and it will inevitably harm U.S. competitiveness on a global level. “There’s a particular danger right now, because the offshore competition American companies are facing is building to a crescendo, a peak, just when we’re becoming more timid,” Nigbor said. “Sarbanes-Oxley is making every U.S. company more timid, less aggressive.”

Boards in the U.S., in particular, have become risk-averse, in part because of the influence of regulators. “There’s an intimidation going on,” said Walter LeCroy, chairman of LeCroy Corp., a manufacturer of electronic wave-shape analysis tools. “The boards are being intimidated by the accounting firms, and you just need to attend some of their sessions,” he said. “I’ll be honest with you, after I attended, I wasn’t sure I wanted to be on my own board. They scare the hell out of people.”

Wary of doing anything to rouse the ire of an Eliot Spitzer, boards are clamping down on growth moves such as acquisitions. Job growth overall will suffer as a result. “People aren’t hiring as many people. They are being more cautious about everything they do,” said Nigbor. “So how do you measure that? How do you go in there and ask, ‘How many jobs are lost because of Sarbanes-Oxley?’”

And how, for that matter, do you measure the impact on the existing work force? Harold Yoh, CEO of diversified managed services firm Day & Zimmermann, suggested that intense dissatisfaction will plague employees at public companies. “And when you have a frustrated employee, you have one who is not going to be as motivated or as freethinking to come up with a better solution,” said Yoh, noting that his private company has been affected because public company customers have stalled projects. “That frustration or de-motivation,” he added, “leads to not being in the game as much. If you’re frustrated, you’re not in the game.”

Those frustrated employees may not want to stick around when and if the job market improves. “All of our employees are kind of ready to leave after four years of being frozen, doing extra work and being asked to do more,” said Barry Siegel, president of Recruitment Enhancement Services. “Now, all of a sudden, Big Brother is watching them, and they’re going to think it’s greener on the other side of the street. They’re going to look for other positions where they think they won’t be watched as much. They can certainly go into the private sector.”

Rather than wade knee-deep in Sarbox paperwork or languish on the open market, many small or midsize companies already have gone private since the new regulation went into effect. And that’s just a taste of what’s to come, assuming the current regulations stay in effect, CEOs agreed. “You’re just going to see an awful lot of smaller public companies that are going private, point blank and simple,” said Maurice Taylor, CEO of wheel-maker Titan International.

Even big companies are fantasizing about the shelter of private life. “I’ve talked with a number of CFOs from companies listed on the [NYSE] who have said to me, ‘If I could easily figure out how to de-list and get off, I’d get off in a heartbeat,’” said Lucent’s Russo. “Those are big, reputable companies we want listed on the exchanges in this country.”

For those opting to stay in the public market—and a mass exodus seems unlikely—the toll will continue to mount. Some CEOs will attempt to gain a business advantage or a return from the investment so that all is not wasted. For example, Cognos’ Ashe noted, one way to leverage more control in terms of management oversight will be to implement more sophisticated tools, such as workflow-based software, document planning systems and transaction controls; those tools will greatly improve CEO visibility into the organization for a number of other purposes.

John Joyce, senior vice president of IBM Global Services and formerly CFO of the computing giant, explained that the company’s investment in standardized systems prior to Sarbanes-Oxley made it much easier to comply. “It was painful, as it was for all of us, with 404, but it was not as bad as we thought because we had so many standardized processes,” he said. “So now that we’ve done 404, and we have this information, it’s, ‘Can we glean business insight from the information that’s flowing?’ We’re obviously going to know more of the details of what’s going on at the end of the supply chain. We now have this information, and the question is now, what can we do with it to help run the company better?”

That’s a bit rosy for some corporate leaders who feel that in the current climate, CEOs resigning themselves to making lemonade would be a deadly passive move. Even obeying the rules won’t keep a CEO out of trouble, they argued. “You get an Eliot Spitzer, and a well-run company, and if the timing is right, the company is just in trouble and becomes a target,” said LeCroy. “So I believe that if business just says, ‘Well, we’ve been dealt a tough hand, but we’re going to make the best of it’—if that’s our whole reaction to this thing, we’re in trouble. I think we need to find some way to push back and convey the message that this is not fair; it’s not good for the country.”

The question remains, How do we get that message across? “How do we collect this experience—what’s good about it, what’s bad about it, agree on what’s bad about it, get into the political process in a way that they understand why correcting it is in their interest,” posed McGrath. “If we don’t do all of those things, we’re going to be sitting here next year and talking about it too.”

Some CEOs, like Ashe, believe that with the 404 compliance date having only just passed, it was still too soon to tally the costs and benefits, or to sort out the impact. “There’s a lot of learning we’re going to accumulate in the next 90 to 120 days, as we find out what the compliance level is,” said Ashe, adding that Ernst & Young has estimated a possible 50 percent noncompliance rate for 404. “If it is 50 percent noncompliance, nobody’s going to care about 404. If it’s 10 percent noncompliance, people are going to care, because those companies are going to be called out.”

Regardless of 404 compliance, what shareholders will be crying about is the diminishing rate of return, predicted Patrick Murray, chairman of Dresser. “When people look at the annual reports this year, and the amount of cost that’s been loaded into these businesses,” he said, “I think it’s going to be sooner rather than later that there’s a backlash.”

One final devilish twist from 404: Auditors have to issue their opinion of a company’s internal controls and whether they can anticipate future misdeeds. If the auditors issue a “qualified opinion,” meaning they have some concerns about a company’s controls, those companies could get pounded in the stock markets or have banks withdraw lines of credit. Depending on how many companies receive qualified opinions, it could be large enough to act as a damper on the overall financial markets.

Add it all up and it’s not a reassuring picture: CEOs will take fewer risks and create fewer jobs at the very moment that global competitors are gearing up. They may postpone projects and their share prices could suffer, all while they are reducing their bottom lines to spend on compliance. When the full enormity of the costs of Sarbox sink in, the pendulum may well swing back—if CEOs are willing to give it a good, firm push.

Still, at least for now, AMD is defying the odds. The company looks as if it will easily hit Ruiz’s server target and has a good shot at grabbing 50% in consumer desktop PCs. Although AMD will probably fall short of its 30% goal in the corporate PC market — a bastion for Intel and its closest ally, Dell Inc. — its multipronged attack is nevertheless sharply boosting sales. Moreover, it will most likely put the company in the black this year for the first time since 2000. For 2004, revenues are expected to surge more than 50%, to $5.3 billion, while net income hits $227 million, according to consensus estimates. In 2005, revenues are projected to climb a further 10%, to $5.8 billion, as profits hit $328 million.

For the first time in the company’s history, AMD wields a potent weapon that makes Ruiz’s ambitious goals more than a wish list. Last year the company took the wraps off the world’s first industry-standard chip that can process data in chunks of either 64 bits or 32 bits at a time, without any performance trade-offs. The chips, dubbed Opteron for servers and AMD Athlon64 for high-end PCs, offer the cheapest possible path to the next level of high-performance computing.

Its success is due in no small part to Intel’s missteps. Intel announced it was working on a rival 64-bit chip, Itanium, back in 1994, about five years before AMD announced plans for its own version. Itanium, however, didn’t hit the market until 2001, two years late, and even then was a huge flop. Intel released a second version of Itanium in 2002, but it was never the hit Intel expected because it required companies to rewrite their existing 32-bit software to take advantage of the new architecture.

That gave AMD an opening. In March of 2003, the company released Opteron. Although it too was delayed, corporations quickly warmed to it because it could handle both the older 32-bit software and new 64-bit applications. That saved companies headaches and millions of dollars in transition costs. “It’s no small fact that, although a small company, AMD is going to drive the architecture for the next generation of microprocessors,” says Banc of America Securities (BAC ) analyst John Lau.

Intel is scrambling to stop that from happening. In July, CEO Craig R. Barrett sent a blistering e-mail to employees saying that the recent execution troubles were “not acceptable.” Barrett and Otellini, who is expected to take over as CEO in 2005, instituted a companywide review of upcoming chips. The result: Intel jettisoned several chips under development, quickly introduced a server chip that could handle 64-bit and 32-bit software, and shifted nearly all of its engineers to work on multiple-core chips for servers, desktops, and notebook PCs. To help jazz up its brand and broaden its marketing message beyond the core PC market, the chipmaker also announced on Sept. 7 it had lured Eric B. Kim, Samsung Electronics Co.’s top marketing exec, to work in the same capacity at Intel. Otellini says the company is “going back to the basics.”

LONE HOLDOUT

One of the key players in the battle between AMD and Intel will be Dell. The Round Rock (Tex.) company is the lone holdout against AMD among the major computer makers. Dell uses Intel chips exclusively in both servers and personal computers, even though IBM (IBM ), Sun, and Hewlett-Packard (HPQ ) have started using AMD’s chips. One reason for Dell’s loyalty is that it derives loads of benefits from the close relationship, including millions in marketing dollars from Intel and early insights into future technologies. Ruiz figures that the only way to persuade Dell to use AMD chips is to win over so many customers that Dell is forced to change. Already, Dell rivals are crowing about the brisk business they’re doing with Opteron servers. “Our Opteron boxes are just flying off the shelf,” says Sun Microsystems Inc. (SUNW ) Chief Executive Scott G. McNealy. A Dell spokesman says it is constantly evaluating suppliers but won’t comment specifically about AMD.

Dell’s reticence is one reason for AMD’s mixed prospects in the PC market. The chipmaker is making progress in consumer PCs, particularly desktop models, because of its low prices. But the more lucrative corporate market is proving much more difficult to penetrate. There, AMD holds only about 8% share and, without winning over Dell and getting more support from IBM and others, that’s unlikely to increase very much.

AMD has also been stymied by product delays at Microsoft Corp. (MSFT ) The software giant originally planned to release a 64-bit operating system this year, but that has been pushed back until the first half of 2005 because Microsoft needed more time to improve security in Windows. The AMD Athlon64 desktop chip, which launched last year, is expected to shine when paired with the software for which it was designed. Microsoft’s delay has given Intel time to fine-tune a competing chip to go with the software giant’s release. Otellini says the chipmaker will have a 64-bit desktop chip when Microsoft rolls out the Windows update.

Perhaps the most difficult task for AMD is building credibility with investors. The chipmaker has a long history of inconsistency. Impressive products often have been followed by flops. Investors remain skittish, despite the strong financial performance of late. The chipmaker’s stock trades at about $11 a share, not far above its 52-week low.

Still, for Ruiz, the company’s improving fortunes and recent success against its nemesis are accomplishments worth celebrating. At a gathering with employees in July, he grabbed his Gibson guitar, introduced Peter Frampton, and launched into an impromptu jam session. “We should have some fun while working so hard,” he says. It has been a long time since an AMD exec could utter such a simple phrase.

By Cliff Edwards in Sunnyvale, Calif.

Other companies haven’t been as fortunate. Take Siebel Systems. When the idea of delivering software as a service emerged as an alternative to selling packages of software, Siebel Systems CEO Thomas Siebel threw his weight behind it. Yet even his influence wasn’t enough. A watershed moment came when Siebel competed against upstart Salesforce.com for the business of tech giant Cisco Systems (CSCO ). Even though Cisco was tilting toward Salesforce.com, (CRM ) Seibel’s sales people pushed traditional product software because they’d get richer commissions that way. Siebel lost the deal, and its business was forced to sell out to Oracle (ORCL ). “There were groups of disbelievers in the organization, which is a recipe for disaster,” says Bruce Cleveland, who ran the software-as-a-service initiative.

GIVE YOUR NEW INITIATIVES ROOM TO BREATHE

A company’s core business and its new initiatives are typically at odds with one another. Force them together, and the old business may well smother the new one. Kodak tried it both ways. For two years it placed the digital camera group within its film business so they could share resources and digital could grow more quickly. But last year it split them off again. “One really couldn’t piggyback on the other,” says Pierre Schaeffer, chief marketing officer for the digital business.

Other companies have scored big by managing their new businesses separately from the start. When Dow Corning conceived of its e-commerce business, Xiameter, the idea was to run it independently. The company didn’t want to devalue the Dow Corning brand, which is equated with premium service. Xiameter was about selling large quantities of silicone at low prices with no services attached. Since its 2002 launch, Xiameter has grown to about 15% of Dow Corning’s total sales.

MAKE PAINFUL BREAKS WITH THE PAST

Switching business models requires a thorough rethinking of everything a company does, from planning to manufacturing to marketing. For 120 years, Kodak had done everything for itself. At one time, it even raised its own cattle and used the bones for making photographic gelatin. When it tried to collaborate with others, the results could be messy. For instance, it sought outside expertise from Adobe Systems (ADBE ) in 1999 when it was developing a product for transferring consumers’ photo prints to compact disks so they could be viewed on PCs. Yet the alliance was fraught with bickering. When Adobe people came up with suggestions, the knee-jerk reaction from Kodakers was “This will never work,” recalls Brian Marks, a 19-year Kodak veteran.

Today, Kodak has had a complete change of heart. In early January, Perez and Motorola (MOT ) CEO Edward Zander stood together at the International Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas and announced a 10-year partnership in which Kodak would provide chips to operate high-quality cameras in Motorola’s cell phones. It was a startling break with Kodak’s past. An organization that had always built its own products would now provide technology for somebody else. Kodak will also help consumers transfer images to PCs or online galleries (75% of all photos never leave cell phones).

Perez is gambling that the match will be well worth all the contortions Kodak is going through. He expects much of the growth in digital photography to happen in mobile phones, and he believes profit margins for sensor chips will be twice those of the digital camera business.

In spite of the changes Perez has made, he admits he still has a lot to do. Old habits die hard. At Kodak, it’s standard procedure to test a new product or service — and then test and test again to make it perfect, even if that stretches out the journey to the marketplace. Case in point: Kodak has been talking up its Scan the World consumer service for a year, but it’s still not sure when or how it will be introduced broadly. The company hopes to sell or lease scanners to photo shops, plus get a piece of the fees charged to customers for the service. Among other things, it’s wrestling with the $50,000 cost of the scanner. Will Kodak be able to adjust quickly enough to meet the demands of new and untried markets? Not clear.

DON’T CONFUSE WHAT YOUR COMPANY DOES WITH HOW IT DOES IT

It is taking time for Kodak to understand that it is an image company, not a film or camera company. Perhaps it should take lessons from Western Union. (WU ) Founded in 1851, the company has managed to ride each successive wave of change in its history rather than getting swamped. (A bankruptcy protection filing in the early 1990s was caused by management mistakes rather than external threats.) After handling the first transcontinental telegram in 1861, it spotted the opportunity to transfer money by wire 10 years later. Then, a series of firsts: a city-to-city facsimile service, a microwave communications system, a commercial satellite network, and online money transfer.

Why has Western Union been able to adapt to severe disruptions and survive over so many years? It never confused the business it was in with the way it conducted its business. At its core, Western Union was about facilitating person-to-person communications and money transfers — whether via telegraph, wireless networks, phone, or the Internet. “We always saw ourselves as a communications company,” says president Christina Gold. Contrast that with Kodak. By defining itself too narrowly as a product company all those years, it was headed for a fall.

Kodak teeters on the precipice, and with it stand some of the other once-great businesses of the 20th century, from autos to newspapers. They were immensely successful and proud, but their very success made it difficult to adjust. “The more successfully you use a way of working, the stronger your culture is, which is a great strength right up to the time when you need to change,” says Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School. All innovation is hard. Reinventing your entire business is the hardest innovation of all.

By Steve Hamm and William C. Symonds

What can we do to reach those goals? Rivet the team’s attention on execution. Discuss the actions, behaviors and processes they’ll need to adopt to attain their goals.

When asking these three questions, appeal to team members’ self-interest. “Explain what’s in it for them if they help the organization identify and achieve stretch goals,” says Desai. “Let them see what their future will look like in terms of reaching their personal and career goals.”

Ask questions in team meetings, but don’t influence the team by revealing your biases. Be willing to listen to even “crazy” ideas. “To avoid intimidating employees, you can have someone else lead the discussion,” Desai added.

Morey Stettner

A Family of Cardiographs and Stress Systems was planned and developed using this approach. The first product release took 25% less time than traditional product development. Since the planning was done for a family, subsequent product releases took only a few months vs. a few years! The value/cost ratio increased by 3X as measured in terms of image quality and ease of use which were the major customer value drivers for the product. Some of the techniques used during implementation of this integrated approach included cross-functional teams, extended team to create awareness and spread the enthusiasm in the entire company, strategic partnerships with customers, customer sessions, market driven innovation and definition, concept definition, design for simplicity, manufacturability and many others.

Any approach towards product development for the future should focus on improving customer value, speed and cost simultaneously in order to achieve success in the global market place. Developing a family of products as described not only does this, but it creates a family of enthusiastic employees too. This approach lights the path of success in the next century, while improving the bottom line dramatically.