How can a food and beverage company that wants to sell 8,500 brands in 86 countries become all things to all customers yet maintain its focus and keep its identity intact? Nestlé CEO Peter Brabeck-Letmathe says it all hinges on the talent that his company nurtures. “We want to make sure that employees at all our regional companies maintain their original cultures, but follow the same Nestlé principles,” says the Austrian-born Brabeck. “We don’t want to transform a Chinese into a Chilean or an American into an Australian. All we’re asking for is that he or she embrace the common values that we have.”

The company’s Management and Leadership Principles state that “people are Nestlé’s most important asset.” It seems to work. “Nestlé puts its money where its mouth is,” explains Robert Hooijberg, professor of organizational behavior at the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) in Lausanne, Switzerland. He says the food giant spends heavily on its high potential managers by putting them through a rigorous program of executive development at Nestlé’s training center in Rive-Reine, not far from the corporate headquarters in the small Swiss town of Vevey.

There, nearly 2,000 junior executives selected from all over the world undergo a monthlong induction into Nestlé’s corporate philosophy, work together on team projects and meet the company’s top brass in groups as well as one on one. Brabeck, 60, spends at least four weeks a year at the training center. He sees it as his key task. “Leadership development,” he says, “is perhaps one of the most important duties that I have.”

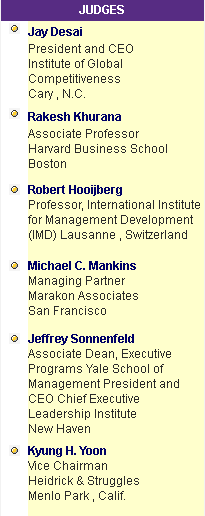

It was Nestle’s commitment to developing leaders that led a panel of judges, including Hooijberg (see list, below left), to conclude at a five-hour meeting in New York that the Swiss company deserved to be cited as the Best International Company for Leadership Development. After two years of examining U.S. leadership development practices, Chief Executive this time cast a wider net, focusing on European and Asian companies. Judges found European practices particularly impressive. “The Europeans have a leg up on their American counterparts,” says Michael Mankins, a judge and managing partner of Marakon Associates in San Francisco. “These companies recognize that developing ‘bench strength’ is the key to unlocking future performance and value.”

Are the Asians Coming?

This year’s Best 20 span the globe from Finland to South Korea and from France to India and Japan. What unites them is the acute understanding that companies based outside the huge U.S. market can compete only if they learn to create different faces to present to a wide range of constituencies. One key point of difference is that some American CEOs think of leadership development and diversity as different objectives. But the European experience, in particular, suggests they are inseparably intertwined. “We are confronted with diversity because there’s no such thing as a united Europe,” says Benoit Potier, chairman of Paris-based Air Liquide, whose company is ranked No. 15. “Diversity has to become a manager’s policy.”

Potier, whose $10 billion company has adopted English as its official language, says that training leadership is so important for a company that operates all over the world because far-flung executives have to understand how to take risks, and when. “We coach people on how to take risks,” he says. “But risk-taking is culture specific. That’s why we need diversity in management. At the same time, not the same kind of management is required in all business environments. So we create an environment profile and match the management profile to it. My task is to place the right kind of people in the right kind of environment.”

Air Liquide has clearly been making the right choices since it’s been around for more than 100 years, says Rakesh Khurana, associate professor at Harvard Business School and another juror on the Best 20 panel. If a company has survived that long, he says, “there’s something in the DNA that’s good.”

Asian-based companies are younger than European multinationals and are therefore different animals. Founding families at Asian companies tend to play stronger roles. Samsung Electronics, for example, is controlled by the Samsung group, which is dominated by the second generation of the Lee family. Yet Chairman Lee Kun Hee “has really placed a huge amount of emphasis on professionalizing talent and bringing in the best and the brightest,” says Kyung Yoon, vice chairman of Heidrick & Struggles and a judge.

As a result, CEO Yun Jong-Yong, a professional manager, has used the various divisions of the company to breed talent so strong that one of his managers, Chin Dae-Je, became Minister of Information and Communications, and Chief Marketing Officer Eric Kim has just been tapped to join Intel. There is, in short, an external market for Samsung talent, which is one of the factors the judges cited in assessing a company’s leadership development.

Toyota, too, is dominated by a founding family, the Toyodas, yet the company has groomed and trained a series of top managers, including current CEO Fujio Cho, who have worked their way up by rotating through a series of international assignments.

Perhaps the most surprising appearances on this year’s Best 20 list are Infosys and Wipro, the burgeoning outsourcing companies in India. These are young companies and are still managed by their founders, yet their embrace of General Electric-style management development techniques has catapulted them into the top tier in a short period of time (see sidebar, left).

Successful internal CEO successions appear to be a hallmark of success. Nestlé has been in operation since 1866 and has had relatively few CEOs over the years. Little wonder, since the average duration of employment at the $70 billion conglomerate is more than 27 years, while the 12 members of the executive board have worked for Nestlé for a combined 349 years. Brabeck himself joined 36 years ago in ice-cream sales and has run the group since 1997. Nestlé puts such a premium on an orderly succession, says Brabeck, that “on the day I became the CEO, I started grooming my successor. And there are several people who are capable of succeeding me one day.”

At Air Liquide, Potier, 47, is young enough that he hasn’t identified a successor. But he says he’ll need to know “at least three to five years in advance” of retirement. Judging by the low turnover rate at the company—at some divisions it’s less than 2 percent—Potier might run Air Liquide for quite a while longer. He’s already been at the company for 27 years.

Potier spends between 20 and 25 percent of his time dealing with human resources issues and tries to get to know as many high-potential leaders as possible. On the whole, Air Liquide’s executive board tends “to have good knowledge of 400 to 450 people at the top level,” he says. “And then we cascade it down to the HR level, where they know everybody in their country.”

Having the right mix of home-grown and acquired talent is a key factor, says IMD’s Hooijberg. He believes the ratio should be around 70 percent home-grown versus 30 percent imported talent. That way, he says, a company can both maintain its corporate culture and make sure it has benchmarked its talent against the best in the class. Air Liquide has narrowly missed this mark: According to Potier, about 80 percent of the company’s mid- to top-level managers rise from within the ranks. But the company is very aggressive in seeking new talent. “We’re on permanent lookout for very young people,” the chairman says, “taking them from universities to train them to become managers.”

If there is a fault line in Europe between those CEOs who manage leadership well versus those who struggle with it, it would appear to be this: The Scandinavians, the Swiss and the Dutch—in short, nationalities whose home markets are small—do a better job than those Europeans whose home markets are much larger, such as Germany, Spain and Italy. It’s noteworthy that four French companies—L’Oreal, Air Liquide, Schneider Electric and Schlumberger—made the Best 20 list while only two German companies did—BMW and Siemens.

Siemens, based in Munich, which is ranked No. 16, in many ways has just carried out a textbook case of CEO succession planning: On January 1, Heinrich Von Pierer is stepping down as CEO of the company, which has more than 400,000 employees, and Klaus Kleinfeld, most recently CEO of Siemens’ North American unit, will be elevated to that job.

The company does, in fact, use most of the traditional development tools, such as 360-degree oral reviews as well as written reviews of the top 500 to 600 managers. But although Siemens is a global company in terms of sales, its management makeup remains very German. All of its executive board members are German, a situation that Jürgen Radomski, management board member responsible for human resources, says “will have to change.” The company fears that high potentials might start looking elsewhere if they see their non-Germanness hampering their career chances.

At the moment it does, acknowledges Radomski. “It would be very hard for a Spanish or a French manager to run this company,” he says. “He would have to be intimately aware of all the German cultural constraints.”

Such corporate monoculture cost Siemens ground in the Best 20 ranking, with jurors pointing out that diversity in the top executive echelon helps attract more and varied talent. At Air Liquide, only half of the executive board is French. At Nestlé, only one of 12 board members is Swiss.

Siemens has been working doggedly at making its corporate culture more international. It has institutionalized country rotations and made sure that all of its top managers have been through several overseas tours of duty. The company runs a large number of training programs, including executive MBAs, at several top U.S. and European business schools. But its development base would have a hard time matching Nestlé’s formidable training ground at IMD, which it has helped found and which it finances generously.

The Swiss simply have refined leadership development practices. According to Brabeck, Nestlé “has three levels of relationship with IMD: first, regular courses for Nestlé employees; then partnership programs where some top IMD professors and Nestlé top executives from one of our business groups work together on a project; and finally, IMD acting as an outside consultant to Nestlé on a specific issue.”

He says that at its Rive-Reine International Training Center Nestlé offers “myriad courses—in finance, marketing at the highest management level and so on. But the most important, fundamental reason for having this center is to use it as a platform for conveying the values and the principles of Nestlé’s leadership.”

To do so, Nestlé doesn’t use outside professors or trainers but rather brings in company management to be the instructors. “We all get involved in these courses,” Brabeck says, “which allows people who come from all over the world to have direct contact with the top management.” Brabeck is against using headhunters to go after external talent. “Our policy is to have home-grown top management,” he says. “But we’re constantly benchmarking against our competitors,” such as Unilever and Danone in Europe and P&G, Kraft, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo in America.”

Jeff Sonnenfeld, a judge who is associate dean at Yale’s School of Management, disputes Brabeck’s view that all European multinationals are more culturally sophisticated than their U.S. competitors. “In his case, that’s true,” says Sonnenfeld. “But you can look at an awful lot of companies that have taken a European colonial power view of the world with very centralized decision-making.” And he notes that very few non-Europeans are CEOs of European companies, in contrast with the U.S. experience of allowing non-Americans to run such icons as McDonald’s and Coca-Cola. The Europeans, it would appear, do not have a monopoly on global leadership.